Japan, 1985, Summer

On July 11, 1985, I set out on my second trip to Japan. I had gone once before in the summer of 1983, taking a wonderful 3-week trip along the Tokaido coast with a group led by my Japanese Language professor, followed by a month of homestays in Shizuoka. The second trip was by myself, and included a short internship in a Japanese company in Shinjuku, another homestay in Shizuoka, a new homestay in the Japan Sea coast town of Toyama, and further travel, particularly to Osaka, Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Kagoshima.

When I arrived in Tokyo, I did the internship at a company called Sophia Systems, and first experienced something that was rather endemic on that trip: people seemed to think I knew what was going on when I didn’t. I should have asked more, but being young and less than industrious in some ways, I failed to ask. And so I muddled through a week or so working in this office without really having any clue of what I was doing there–what I was supposed to do, to produce. They set me up in an apartment building/dormitory in Kitano out near Hachioji, and every day I commuted in to Shinjuku with the other workers, to an office in the NS Building. At that time, West Shinjuku was only half-developed, some of the now-signature buildings not there, only empty lots in their place.

I would come in to the office and they would give me English translations to proofread. I did that for the time I was there, but not having been given instructions by my professor, who had set this up, and not told more than the basics by the people at the office in Tokyo, I just did the work and muddled along. Years later, my Japanese professor asked why I had not filed the kind of report she expected, and the only reply I could give was, you never told me what I was supposed to write about. I did what I could, commenting on what I could observe of the cultural differences, but it was not much. The main detail that sticks out after all these years was my ongoing race with the office ladies and the refreshments cart. I was uneasy being served by others, but they were uneasy having any of the office workers get things for themselves. I would usually wait until they were otherwise occupied, and then dash off for a drink before they could intercept me and insist on getting it for me–which they usually did.

After Tokyo, I went to the town of Iwata in Shizuoka Prefecture. The town is now famous for the soccer team Iwata Jubilo based there, but when I was there (both in 1983 and in 1985), it was just a countryside suburb of Hamamatsu City. The only event of note when I was there was that when I announced my plans to travel in Kyushu later on, my host mother insisted on arranging me to take a bus from Nagasaki to a transit point I forget the name of, on the way to Kagoshima.

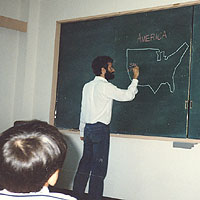

From Iwata, I made my way to Toyama, where my professor knew the head of the local YMCA. In exchange for a homestay at the homes of a few students, I guest-lectured at the Y’s English school, which is to say I just stood up and talked, providing language practice for the students there. It was there that I learned about careers in language teaching, and that experience changed my life. At that point, I had just finished more than two years at a community college, majoring in Japanese Language, and had been accepted to U.C. Berkeley for the following January. But the idea of being able to spend a year in Japan, living and working, greatly appealed to me; I was much interested in applying and adding to what I had learned already. However, I did not make any serious plans to do so–it just appealed to me, and I mentioned that to the staff when I was there. More on that later.

From Iwata, I made my way to Toyama, where my professor knew the head of the local YMCA. In exchange for a homestay at the homes of a few students, I guest-lectured at the Y’s English school, which is to say I just stood up and talked, providing language practice for the students there. It was there that I learned about careers in language teaching, and that experience changed my life. At that point, I had just finished more than two years at a community college, majoring in Japanese Language, and had been accepted to U.C. Berkeley for the following January. But the idea of being able to spend a year in Japan, living and working, greatly appealed to me; I was much interested in applying and adding to what I had learned already. However, I did not make any serious plans to do so–it just appealed to me, and I mentioned that to the staff when I was there. More on that later.

While there, I again experienced the no-one’s-telling-me-anything malaise. During my stay, there was a YMCA event, a nature camp outing for mentally handicapped children. It was quite enjoyable and the children were sweet, but I was not given the slightest clue of what I was supposed to do. One evening, there was a long meeting I was asked to attend. However, the meeting was completely in Japanese–I was the only non-Japanese there–and there was no mechanism to translate for me. After about a whole hour of being unable to understand what was going on, I got tired of the uselessness of it all and wandered back to my room. I was later chastised for leaving the meeting, but I had a good excuse: there was no point whatsoever for my being there. Between that event and the internship uncertainty, I developed a feeling that it is assumed in Japan that you always know what’s happening, and no one tells you anything unless you ask, even when you might not even know to ask. I did experience that some times in Japan in the early years, but never figured out if it was just me, which it probably was.

After Toyama, I traveled down to Osaka. I forget what I planned to do there because I was not able to get it done; I had picked up some nasty bug from one of the kids at the camp, and was confined to bed for my few days in the city (I stayed at a youth hostel while there, mostly sticking to my bunk). Fortunately, the malady abated in time for my scheduled departure. From there, I went to Hiroshima. I had been there before in 1983, but had departed from my tour to meet a pen pal from that time. My pen pal had shown me the Hiroshima Atomic Park and the Peace Dome (the preserved remains of the domed building near ground zero), but that was it. I had not even been aware at the time that there was a museum on the site, and so I had missed it. This time around, I wanted to get the whole tour. I did, and I am glad I made the stop.

After Toyama, I traveled down to Osaka. I forget what I planned to do there because I was not able to get it done; I had picked up some nasty bug from one of the kids at the camp, and was confined to bed for my few days in the city (I stayed at a youth hostel while there, mostly sticking to my bunk). Fortunately, the malady abated in time for my scheduled departure. From there, I went to Hiroshima. I had been there before in 1983, but had departed from my tour to meet a pen pal from that time. My pen pal had shown me the Hiroshima Atomic Park and the Peace Dome (the preserved remains of the domed building near ground zero), but that was it. I had not even been aware at the time that there was a museum on the site, and so I had missed it. This time around, I wanted to get the whole tour. I did, and I am glad I made the stop.

The museum is not a pleasant place, but then it is not supposed to be. Quite grim, but significant and sometimes fascinating, the museum displayed the story of the bombing through models, photographs, and exhibits of melted and twisted items, as well as other objects like the bank steps where the shadow of someone who sat there when the bomb went off is preserved. It’s a stop that should be required for anyone, but especially for Americans, whatever your opinion is about whether the bombing was justified. This is not something you can just find out about in a removed sense. Coming out of the museum, I was greeted with a scene of almost jarring discordance: break dancers were performing near the exit. This was the mid-eighties.

After Hiroshima, I made my way to Nagasaki, not just for the second atomic bomb park and museum, or for the historical tour regarding the city’s long past contact with the West. It happened to be O-Bon time in the city, and I got to experience the festival, from the parades and floats in the evening streets exploding with firecrackers, to the issuing of the candle floats in the water to memorialize the spirits passed. I believe I still have a primitive wooden mallet used to hit gongs in the parade that someone presented to me.

After Hiroshima, I made my way to Nagasaki, not just for the second atomic bomb park and museum, or for the historical tour regarding the city’s long past contact with the West. It happened to be O-Bon time in the city, and I got to experience the festival, from the parades and floats in the evening streets exploding with firecrackers, to the issuing of the candle floats in the water to memorialize the spirits passed. I believe I still have a primitive wooden mallet used to hit gongs in the parade that someone presented to me.

Leaving Nagasaki, I took the bus tour that my Shizuoka host mother had arranged. In our spotty communications, I had tried to impress on her that I needed to get from Nagasaki to Kagoshima by a certain time, that the hostel where I was staying only accepted visitors up to a certain hour. She insisted that I take the bus, saying it was the fastest way to where I was going–so naturally I assumed it was a transit bus. It wasn’t. It was a tour bus that made frequent long stops along the way, at tourist spots I neither understood nor was interested in in the slightest. So I spent much of the time looking at my watch and bemoaning the fact that the tour was taking me not only too much time, but was circuitously taking me away from any train stations where I could depart the bus and get back on schedule. I am sure that my host mother meant well, but she did understand well enough to know that I was on a tight schedule, and despite her ability to speak English just well enough, she never told me that it was a sightseeing bus or what exactly the sightseeing was about. I don’t know, maybe even she didn’t know.

FInally, the tour ended and I got on a train for Kagoshima and I believe I made it there on time. Kagoshima was fine, but dusty–the nearby volcano was pluming and there was ash everywhere. You would have to shake it out of your hair every time you came indoors. After Kagoshima, I went home via Tokyo and a four-day stay in Hawaii. It was the end of August.

It was a few weeks later that the Toyama visit came back to change everything I’d planned, setting me on a completely different path in life, but that story is for another post soon.

That is a very interesting read. I think I’ve been in Japan for about the same amount of time and I did experience the no one is telling me what to do thing. But after awhile you become more sensitive to your surroundings and you eventually learn to sense what people expect. I learned that lesson the hard way. I was waiting tables in a chinese restaurant for 14hours a day with a manager that kept yelling at me because I didn’t do what he wanted even though he didn’t tell me to. BTW, I have some old pics on my blog if you’re interested have a look

http://blog.q-taro.com/archives/000878.php

http://blog.q-taro.com/archives/000890.php

Roy: thanks, and some interesting photos there. I was in Toyama for two years and did not get down to Tokyo till Fall 1987. I think I have some photos from that time, but probably not too many of the basic scenery. Still, it might be fun to go around and take follow-up shots like you did…