I was just recently reminded of a story I haven’t told on this blog yet, so here goes. There was a case twenty years ago concerning a Japanese woman living in Los Angeles named Fumiko Kimura. In 1985, Kimura, her husband and two children were U.S. immigrants in Santa Monica, CA. At one point, Kimura discovered that her husband was having an affair. Distraught, she eventually decided to commit suicide. She took a bus to the beach with her two children and walked them into the surf. The children drowned, but Kimura was rescued before she died. Back when I lived in Japan and this was a story in the news, I read about it and was more familiar with the case than I am now; I know there were more details (for example, I believe she was found by a couple jogging on the beach, one or both of whom were med students), but I can’t recall them all nor can I readily find more details on the Internet. But the story still has very interesting aspects.

You see, Kimura was charged with the first-degree murder of her two children, and it was argued that cultural considerations should be taken into account: in Japan, oyako shinju (親子心中) sometimes happens when a woman decides to commit suicide and takes her children with her. I’ve heard it explained in two ways: the first is that the mother feels so strongly that her children are a part of her, if she decides to commit suicide, leaving her children behind would be like leaving her arms or legs behind. The second, most commonly recounted on the Internet (which may have a single common source that just got repeated) is that it would be unthinkable to leave her children to suffer the shame she is leaving. Both may be true, I don’t know. But it does happen, and in Japan, it has been known to merit a lenient sentence.

The case prompted an outpouring of support from the Asian-American community, where her feelings and actions, if not necessarily approved of, were at least better understood; a “Fumiko Kimura Fair Trial Committee” was formed, 25,000 names were signed to a petition asking for leniency. It was argued that it was her culture, the way she was brought up, the way she thought and believed.

Her lawyers, however, argued this not wholly as a cultural defense (which would have required Kimura to be thinking clearly and believing what she did was right, not a good legal argument in the U.S.) but that it was a case of temporary insanity with cultural connotations. Six psychologists testified to that effect, using in part as evidence that she could not differentiate her life from her children’s. (Interesting–were they stating that a cultural view was a type of insanity?) The culture/insanity defense sounds like a wink-wink kind of strategy, trying to have it both ways–I’d love to see the court transcripts to see how it was argued.

In the end, the court did not decide: a plea bargain was worked out, where Kimura pled guilty to voluntary manslaughter (on the premise there was no malice), and was released on time served (she had spent a year in jail while her case was prosecuted), with five years’ probation and mandatory counseling. She later reunited with her husband.

A few years later, a Japanese television network decided to make a TV movie based upon the incident; it was broadcast bilingually, with an English audio track over a Japanese-language television movie, something that rarely if ever happened. I looked forward to the movie. At that time, I was still in my funk about foreigners being looked down upon in Japan, seen all too often in the media as violent criminals or disease carriers. One drama show had a couple visit Hawaii, only to become victims of five violent crimes within a few days. My students back then were fearful to travel to the U.S. because of the idea of the U.S. being too violent–more fearful than they are today about terrorism, in fact. There was even a Japanese man who wanted to kill his wife, and so traveled with her to America; he had her killed there, counting on the specter of a violent America to remove suspicion from himself (I can’t find this anywhere, does anyone remember his name?). At first it worked, with Japanese and Americans believing it, until the truth was found out.

[Update: found it. It was Kazuyoshi Miura, who first allegedly tried to kill his wife, Kazumi, in 1981 in Los Angeles by having his soft-porn actress girlfriend beat Kazumi over the head, and then a few months later Kazumi was shot dead (with Kazuyoshi lightly wounded in the leg). Kazumi lingered in a coma for a year and then died, and Miura received 80 million yen from two insurance policies he’d placed on his wife with him as the beneficiary. The case, as I recall, spurred a great deal of “America-is-violent” reactions in Japan, which Miura allegedly used to divert suspicion from himself. It seems to have worked, until in 1984 when a weekly magazine identified him as the killer. He also allegedly had a girlfriend killed in Los Angeles in 1979. He was charged with the beating incident in 1985 and the murder in 1988; he was eventually sentenced to life in prison in 1994, but was acquitted on appeal in 1998, which was upheld by a higher court in 2003. Last heard from, he was arrested for shoplifting in 2003.]

So at that time, I looked forward to the dramatization of the Kimura case; it had a good many positive aspects that could be brought out in the telling. The personal drama and the cultural differences would have been compelling–but it could also show America to Japan in a better light, as a country trying to understand and accept various cultures, in contrast to stereotyping and discriminating.

Boy, was I let down. The movie, titled “The First-Degree Murderer of Los Angeles” (ロスの第一球殺人, or Rosu no Dai-Ikkyu Satsujin), was “based upon a real story,” but trashed the reality, changing everything to reinforce the stereotypes I had hoped it would help dismiss. I know, what should I expect and all, but I didn’t think they’d go as far as they did. The central elements–a Japanese woman in America, her husband wrongs her, she commits oyako shinju and is charged with murder–were still there. But the rest was unrecognizable.

In the TV movie, Kimura had only one child (the reason will become apparent later), a small boy, and had come to America with her husband, who ran a construction firm or some other kind of like business. She spoke no English and was totally isolated, alone with her son. The filmmakers went to great length to make her into a heroine; for example, in one scene, she rescued someone else’s child from being run over by a motorcyclist (more on that later). One day, her husband did not return home. In the story, he ran off with the payroll for his business, leaving the American workers without pay. She hoped and hoped and hoped he’d return, but he never did. She started to run out of money, and the blue-collar workers at her husband’s firm came by all the time, banging on the door and screaming for their money, with our protagonist huddling fearfully with her small boy inside the locked house.

Finally, without anyone to help, her money running out, losing hope her husband would ever return and living in fear every day, she decided to commit oyako shinju, killing her son first and then killing herself. So she went to her boy’s room to smother him with a pillow. But while she was doing it, her boy laughed, thinking it was a game. Suddenly, she was overcome with love for her boy, and so instead of killing him and committing suicide, she heroically decided to brave it out and persevere. So she went to the kitchen to prepare her son’s favorite deep-fried dish. After she got the burner going under the pot of oil full-blast, the doorbell rang. It was her husband! she thought–he’s back and everything will be fine now! But when she went and opened the door, it was two big, burly American men who were looking for her husband. They threw her roughly to the floor and after not spotting her husband around, naturally decided to violently rape our protagonist.

As they were doing this, the pot of oil boiled over, and within half a minute the entire kitchen was on fire. When the two blue-collar-workers-turned-rapists saw the smoke, one shouted “let’s get outta here!” and they both fled, leaving our heroine beaten and senseless on the living room floor. As the smoke filled the house with incredible speed, the son called out for help. This brought our heroine out of her stupor; she valiantly got up and tried to rescue her son, putting her hand over his mouth and nose to protect him from the smoke. However, somewhere along the fifteen feet from his bed to the front door, she collapsed, her hand still covering his mouth.

Firefighters came and pulled them out. The boy had died from suffocation. They found her suicide note and assumed she had killed her son. She was charged with first-degree murder, and despite her story of the rapists and her sterling reputation as a child rescuer, an American jury found her guilty and sentenced her to two years in prison.

So you can see how I was disappointed. The relevance of oyako shinju and the cultural relativism were completely removed, and instead of an America sympathetic to other points of view, we again see a violent America inhospitable to Japanese who would dare go there. The motorcycle incident was one element of this, though indirect. The scene was shot so that the small child in danger was in the middle of the street, and the motorcycle was bearing straight down on the child from a distance, with no turns or obstacles to make it seem like an accident. It was not a car with the driver distracted; it was not a case of the child suddenly running out into the street from behind a parked vehicle. It was a motorcyclist apparently intent on running down the child. Why do that, making it seem as malicious as possible, when it would be far easier to make it seem like an impending accident?

The film recast the Japanese character into a heroic, selfless, and sinless heroine with few if any faults, and Americans as the villains (her husband simply absent from the scene). The guilty sentence at the end does not make sense and seems a callous slap in the face, and all possible positive or redemptive qualities of the story were removed and replaced with base, discriminatory stereotypes. And unfortunately, it was more or less the rule and not the exemption for Japanese media at the time.

Today, things are a lot different, as I have pointed out before. It would be interesting to see the same story told again, this time from a more constructive and realistic point of view.

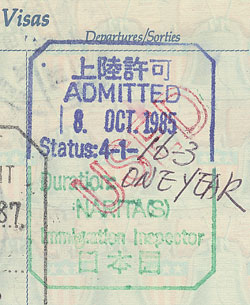

Soon afterwards, I was introduced to my apartment (a bare-concrete-walled 6-mat room with a unit bath and a hallway kitchenette, with no windows except the balcony doors, and was soon to be overcome by mold) and my job. It offered a minimal salary–210,000 yen a month, plus 40,000 yen for the apartment rent. And the Y never compensated me for the extra few hundred bucks that the longer-flight ticket cost me, despite the fact that they not only caused me that excess expense but very nearly cost me much, much more. I wanted to rant at them, but it being my first time living and working in Japan and wanting to build a good relationship with my employer–not to mention that they made it clear they would never pay–I decided not let it go. Alas, that was not my last problem with that particular branch or its management at the time. Like when they ripped me off on the apartment’s key money (they said I would pay “half,” but didn’t tell me that I was paying the non-refundable half while they paid the refundable deposit–though they made me move when I left their employ, retaining ownership of the lease), or when they essentially stole $700 I made teaching on a side job (“Thank you for the donation”), or when they threatened to deport me when I complained about the lost wages. I could make a whole other blog post about it, but I probably won’t.

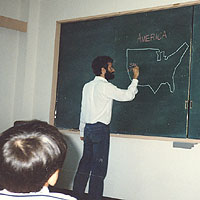

Soon afterwards, I was introduced to my apartment (a bare-concrete-walled 6-mat room with a unit bath and a hallway kitchenette, with no windows except the balcony doors, and was soon to be overcome by mold) and my job. It offered a minimal salary–210,000 yen a month, plus 40,000 yen for the apartment rent. And the Y never compensated me for the extra few hundred bucks that the longer-flight ticket cost me, despite the fact that they not only caused me that excess expense but very nearly cost me much, much more. I wanted to rant at them, but it being my first time living and working in Japan and wanting to build a good relationship with my employer–not to mention that they made it clear they would never pay–I decided not let it go. Alas, that was not my last problem with that particular branch or its management at the time. Like when they ripped me off on the apartment’s key money (they said I would pay “half,” but didn’t tell me that I was paying the non-refundable half while they paid the refundable deposit–though they made me move when I left their employ, retaining ownership of the lease), or when they essentially stole $700 I made teaching on a side job (“Thank you for the donation”), or when they threatened to deport me when I complained about the lost wages. I could make a whole other blog post about it, but I probably won’t. From Iwata, I made my way to Toyama, where my professor knew the head of the local YMCA. In exchange for a homestay at the homes of a few students, I guest-lectured at the Y’s English school, which is to say I just stood up and talked, providing language practice for the students there. It was there that I learned about careers in language teaching, and that experience changed my life. At that point, I had just finished more than two years at a community college, majoring in Japanese Language, and had been accepted to U.C. Berkeley for the following January. But the idea of being able to spend a year in Japan, living and working, greatly appealed to me; I was much interested in applying and adding to what I had learned already. However, I did not make any serious plans to do so–it just appealed to me, and I mentioned that to the staff when I was there. More on that later.

From Iwata, I made my way to Toyama, where my professor knew the head of the local YMCA. In exchange for a homestay at the homes of a few students, I guest-lectured at the Y’s English school, which is to say I just stood up and talked, providing language practice for the students there. It was there that I learned about careers in language teaching, and that experience changed my life. At that point, I had just finished more than two years at a community college, majoring in Japanese Language, and had been accepted to U.C. Berkeley for the following January. But the idea of being able to spend a year in Japan, living and working, greatly appealed to me; I was much interested in applying and adding to what I had learned already. However, I did not make any serious plans to do so–it just appealed to me, and I mentioned that to the staff when I was there. More on that later. After Toyama, I traveled down to Osaka. I forget what I planned to do there because I was not able to get it done; I had picked up some nasty bug from one of the kids at the camp, and was confined to bed for my few days in the city (I stayed at a youth hostel while there, mostly sticking to my bunk). Fortunately, the malady abated in time for my scheduled departure. From there, I went to Hiroshima. I had been there before in 1983, but had departed from my tour to meet a pen pal from that time. My pen pal had shown me the Hiroshima Atomic Park and the Peace Dome (the preserved remains of the domed building near ground zero), but that was it. I had not even been aware at the time that there was a museum on the site, and so I had missed it. This time around, I wanted to get the whole tour. I did, and I am glad I made the stop.

After Toyama, I traveled down to Osaka. I forget what I planned to do there because I was not able to get it done; I had picked up some nasty bug from one of the kids at the camp, and was confined to bed for my few days in the city (I stayed at a youth hostel while there, mostly sticking to my bunk). Fortunately, the malady abated in time for my scheduled departure. From there, I went to Hiroshima. I had been there before in 1983, but had departed from my tour to meet a pen pal from that time. My pen pal had shown me the Hiroshima Atomic Park and the Peace Dome (the preserved remains of the domed building near ground zero), but that was it. I had not even been aware at the time that there was a museum on the site, and so I had missed it. This time around, I wanted to get the whole tour. I did, and I am glad I made the stop.  After Hiroshima, I made my way to Nagasaki, not just for the second atomic bomb park and museum, or for the historical tour regarding the city’s long past contact with the West. It happened to be O-Bon time in the city, and I got to experience the festival, from the parades and floats in the evening streets exploding with firecrackers, to the issuing of the candle floats in the water to memorialize the spirits passed. I believe I still have a primitive wooden mallet used to hit gongs in the parade that someone presented to me.

After Hiroshima, I made my way to Nagasaki, not just for the second atomic bomb park and museum, or for the historical tour regarding the city’s long past contact with the West. It happened to be O-Bon time in the city, and I got to experience the festival, from the parades and floats in the evening streets exploding with firecrackers, to the issuing of the candle floats in the water to memorialize the spirits passed. I believe I still have a primitive wooden mallet used to hit gongs in the parade that someone presented to me.