Andrew Sullivan is revisiting his mistaken support for the Iraq War a decade ago:

This month, the tenth anniversary of the beginning of the Iraq War, I’ve decided to re-publish some of my posts from March 2003. Call it masochism or basic journalistic accountability or the Internet’s revenge. But I was wrong. I was wrong in good faith. But I was wrong.

He is among some right-leaners to outright right-wing war hawks who are looking back. What comes across is not just that they feel they were wrong for the right reasons, but that the anti-war side was hysterical and completely without reason. Ta-Nehisi Coates ruminates:

It seemed, back then, that every “sensible” and “serious” person you knew — left or right — was for the war. And they were all wrong. Never forget that they were all wrong. And never forget that the radicals with their drum circles and their wild hair were right.

But, Coates expresses, not sensibly enough. Rod Dreher concurs:

I covered a big antiwar march in Manhattan in the spring of 2002, and the radicals were a disgusting bunch. “Bush = Hitler” signs, and so forth. As foul as it was, the event was a pleasant thing to see, in a way, because it made me feel more secure in the rightness of the war the US was about to undertake. And it shouldn’t be forgotten in those days that some antiwar people were nasty and hysterical, and impossible to talk to.

For all that … they were right about the only question that counted — Should the US launch a war on Iraq? — and my side was wrong. I was wrong. I had allowed myself to be swayed by emotion, even as I spited the emotional hysteria of the antiwar crowd.

From the linked-to 2003 article:

I’ve tried to think through my pro-war position carefully, and if I’m wrong in my facts or analysis, I want to know. But in my (deeply unpleasant) experience, there’s simply no point in talking to most antiwar people, left and right, because they’re lost in a fever swamp of emotionalism.

If it’s not leftists obsessing about “blood for oil,” corporate plots and Iraqi children, it’s rightists going off about imperialism, Israel and Jewish conspiracies. Now, I don’t think it’s unfair to discuss the role, if any, corporate interests, Israeli government policy, the potential suffering of Iraqi civilians, or a number of other issues have in the development of U.S. policy towards Iraq. It’s just that so many people concerned with these things have given themselves over to the kind of hysteria that makes rational debate impossible.

So I have to wonder: did I sound hysterical back then? Because I wasn’t the only one citing arguments such as my own. The opinions I forwarded were actually fairly prominent in the anti-war crowd.

These apparently repentant former hawks remember things differently, almost using the radical hysteria they cite as an excuse for the wrong decisions they made. They give the clear impression that the anti-war side had no reasonable-sounding arguments.

I still have my original “blog” posts, back before I found Movable Type and WordPress, where I made the pages one by one with a web page editor. I was just so upset about the impending war that I had to express myself.

At the time, I had the motivations for war at least partly incorrect: I felt the major impetus for Bush was to hold on to the fantastic surge in popularity he enjoyed after 9/11, and the resulting political capital it gave him. Bush was unusual because for the most part of his presidency his popularity sank with almost machine-like regularity, buoyed only by major events (9/11, the beginning of the Iraq War, and the capture of Saddam). Driving up popular support and translating that into political capital was indeed one element of the drive for war, but certainly not the main one, which now appears to have been geopolitical, to assert control over a major oil-producing region, as well as dynastic, in the sense that the Cold War was over and the military industry needed new fuel and the pols a new foe.

My main screed against the war was in this post from August 2002, however. So let’s see how hysterical I was.

I was right and wrong on a central issue:

The arguments for getting Saddam out of power are easy: he’s a dangerous madman, and we could overwhelm the Iraqi military. But the question is not should Saddam go, or could we win in a limited conflict: the question is, how can we do this without bringing about catastrophe? Imagine that rats have infested your home. There is no question that they must go; but do you exterminate them by taking a flamethrower to the building? Method is crucial.

I was wrong in that I felt Saddam had to go. He was a tin-pot dictator, and those are a dime a dozen. After the first Gulf War, he was beaten down and contained. His utility in holding the different sects within Iraq relatively stable probably outweighed any risk he presented.

Otherwise, I was very much correct: from the beginning of my writing, I centered in on what would become the central issue of the war: method and management.

I stepped back and made these general points in the argument against going to war:

- There was not enough international support

- The cost would be prohibitive

- We would take a body blow to our reputation

- We would violate our long-held no-first-strike policy

- The war could escalate and set fire to the region

I was right on the first one; the “Coalition of the Willing” was a joke. It was the U.S. and the U.K. with a few scattered allies. We denigrated the nations that refused to go along (remember how Congress idiotically banished french fries?), which didn’t help things much.

I was also right on the second one, but to an embarrassingly modest degree. I cited an $80 billion cost.

I was right that it damaged our reputation; though the costs are not outwardly apparent, it’s pretty obvious that while respecting our power, the world has far less respect today for our judgment.

I was right about violating our policies against instigating war… and no one still seems to give a damn. A new age.

I was wrong on the escalation; while the war did inflame Iraq and set off a civil war, it did not come close to the conflagration I warned was likely. Glad to be wrong on that, but was I hysterical on that point? I could probably appear that way, especially if you focused on that and ignored the rest.

The rest included my next series of points, on reasons not to believe the hype:

- I stated that Cheney was lying about Iraq’s nuclear program and there was no evidence that Iraq was any nuclear threat at all; I noted similar false claims from the first Gulf War.

- I noted that Bush needed Congressional approval. (They later gave it, making this point moot.)

- I noted that the claims linking Hussein to terrorists were false.

While the second point became moot, I was perfectly accurate on the first and last. Cheney was lying, and there was no link to al Qaeda.

Finally, I made my closing argument:

And then we come to the end game: what is the exit strategy? How long will it take? How many of our troops will die? How many Iraqis (whom the Bush Jr. administration claims to be acting to benefit) will we end up killing? How long will our troops be there? How deeply will we become involved in rooting out everyone there who violently disagrees with our occupation? And how will the nation-building succeed? What guarantees do we have that the moment we extract ourselves, another Saddam Hussein won’t pop up again and bring us back to square one? As far as I can determine, not a single one of these questions has been answered.

If that’s not enough still, then ask yourself: in the Gulf War, why did we not follow through and get Saddam then? What stopped us? There are many answers to that question, but hardly a one of them is less valid today than it was a decade ago. What stopped us then will not stop us any less today.

Tell me how hysterical I was. How I was not “sensible” or “serious.” How I was incapable of “rational debate.” Go ahead.

I predicted the lack of an exit strategy and asked how long our troops would be there: spot on. The war lasted a decade.

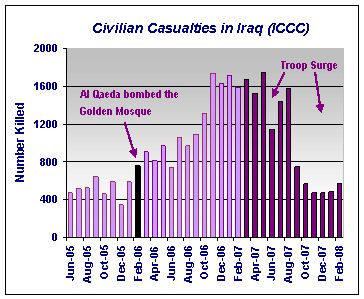

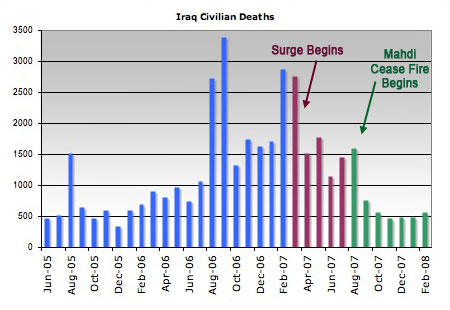

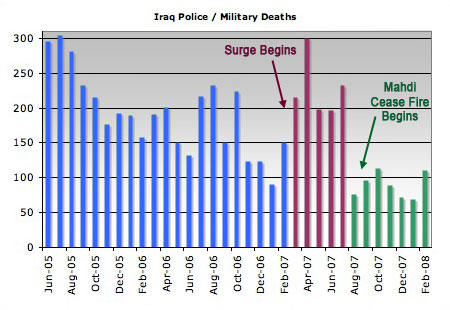

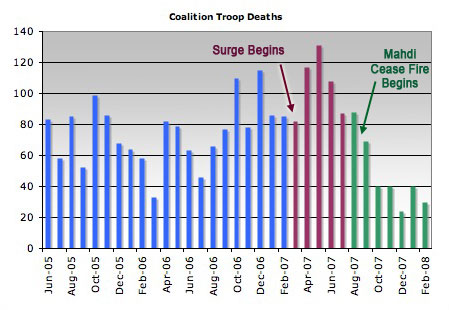

I predicted the toll on the soldiery. 4488 died.

I predicted the cost in civilian lives. The documented number is 110,000 to 120,000, and the real number is likely far higher.

I predicted the futility of nation-building: does anyone feel that Iraq is now rock-solid? It took us a decade to feel confident enough to leave, but we leave hardly confident in the long-term stability of the government.

In short, these two paragraphs, my focus on method, planning, and outcomes, could hardly have been more prescient unless I had somehow magically predicted the specific blunders committed by the Bush administration.

Alas, I then conclude with my three errors: that Bush was only seeking a boost in the polls, that Saddam had to go, and that it could lead to even a nuclear conflict in the Middle East.

Did I, and the many people making similar arguments, sound hysterical? Only if you carefully choose which specific arguments to note, or which voices of protest to even listen to. If you only singled out the easiest points to disagree with, or if you only paid attention to the conspiracy theorists, then you could feel there was a case for how the other side was not reasonable. This, however, is dishonest; the greater part of the movement against the war made sound, salient points, and correctly tried to warn against the grave errors we were about to commit.

There was great doubt about the motives for going to war; that was correct and reasonable. There were many voices doubting the “facts” we were being presented; that was more correct than even we knew at the time. There was the argument that it would cost too much; again, we were more right than we could have guessed. There were concerns about quagmire and drawn-out conflicts; we could not have been more right.

To reduce the anti-war movement from that time to “drum circles with wild hair” who were “nasty and hysterical, and impossible to talk to” is revealing not of the anti-war movement but of the pro-war movement. Even today, when supposedly recalcitrant, they completely omit the presence of rational people, in great numbers, who made sensible arguments that proved true over time, and instead contrast their former positions with the extremists only.

…every “sensible” and “serious” person you knew — left or right — was for the war.

It’s easy to say that when you shallowly dismiss anyone opposed to your point of view as not being sensible or serious, instead lumping them all together with the extremists.

As foul as it was, the event was a pleasant thing to see, in a way, because it made me feel more secure in the rightness of the war the US was about to undertake.

This sums up the righteous smugness of the pro-war crowd: I can dismiss all who disagree with me instead of confronting and answering the grave and serious challenges forwarded by reasonable people.

Yes, there were lots of people shouting “No War for Oil.” You know what? Oil did have something to do with it. Obviously. Yes, there were conspiracy theorists. You know what? They were in the minority.

Sorry, but you can’t be repentant by half-blaming your bad decisions on straw men.

You know what would be a genuine expression of regret? Citing the people that warned correctly, noting how and why you chose to dismiss their arguments, explaining how and why you believed the falsehoods and validated the liars, and making a sincere statement about not dismissing such warnings or believing the hype in the future. Write that essay, and I will feel that you will be less likely to err again in the future.

Instead, these people gloss over the details of their errors and instead continue to focus on how unreasonable the other side was. They admit to gross errors, but remain blind to the mechanism that led to them.

The word “hysteria” is often used to describe the anti-war movement. There was hysteria enough to go around to be sure, but very little was coming from the rational crowd against the war. The real hysteria, one these now-penitent hawks seem still blind to, was the quiet hysteria of fear, pride, and patriotism that allowed them to abandon reason and believe the obvious lies that were being served to them. “Hysteria” is defined as “exaggerated or uncontrollable emotion or excitement” in a group of people. That perfectly describes what drove the pro-war movement.

It’s just that so many people concerned with these things have given themselves over to the kind of hysteria that makes rational debate impossible.

Funny. That was my impression of the pro-war crowd. We were talking about the lack of convincing evidence, while you guys were buying patently false evidence and demanding immediate action; we were talking about how Hussein was not seriously armed while you guys were claiming Hussein obviously had WMD because he threw out the inspectors (which he didn’t); we were asking about cost in dollars and lives while you guys were saying it would be a cakewalk and that Iraqi oil would pay for the negligible bill; we were asking about exit strategies while you guys were glibly insisting that Iraqis would throw flowers at our soldier’s feet.

And, after time has proven us right and you wrong, you have the utter gall to claim that we were emotionally hysterical, impossible to talk to, and incapable of rational debate?

Go frack yourself. You were the hysterical ones—and that was what truly drove us to war. The fear of terrorism after 9/11, and the atmosphere that dominated in which one had to be gung-ho or else you were “not with us” and therefore “against us.”

There were many, many voices of reason who were very much right about the reasons not to go to war. I don’t give a crap about what Clinton said at times. Pols will speak to what’s popular and easy; the politicians were not, for the most part, the heart of the anti-war movement. Nor was the anti-war movement marked by the crazies, rather the crazies were used to denigrate the reasoned and reasonable opposition. We were all treated as blind idiots or dangerous traitors, impossible to reason with.

And even after all that has happened, the people who were so clearly wrong in foresight and in hindsight still make the same false claims about those they disagreed with, still use them as a false foil to assuage their guilt and remorse.