Downtown Shanghai

Due to a combination of matters of convenience and difficulty, I’ve decided not to take the side trip to Beijing this time around. Mainly it’s due to limited time. Though the span of this trip is ten days, the first day I got here late evening and the last day I’ll leave early morning, so it’s really eight days. Traveling to an from Beijing would take the better part of a day each way, and so in the end 10 days would get pared down to 6 and change; either I’d spend too little time in Beijing or too little in Shanghai, and the side trip would add several hundred dollars to the trip cost, seeing as how I’d have to pay for plane fares and hotels for two. So it’ll just be Shanghai this trip.

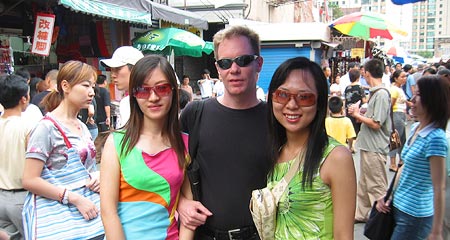

In any case, the itinerary for the second day was seeing people, dining, and shopping. First stop: Xujiahui (pronounced Shoe-jaw-hweh), where we went to Starbucks and were able to log on–though the connection was even slower than at the local Internet cafe. Then we met up with two more of Ken’s friends, girls going by the English names Kitty and Flavour (Ken tried to talk Flavour into using the name Isabella, but she really prefers Flavour). Then it was off to the Oriental Market at Xiang Yang, a maze of stalls selling stuff at very cheap prices, so long as you negotiate well.

Flavour, Ken and Kitty at Xu Jia Hui market

As you walk through the area, the level of people reaching out to you, following you around, and calling after you rises far above the normal street level of this activity. And if you should happen even to pause to look at some stall, much less show interest in a specific item, the stallkeeper will jump out and start the sales process. First lesson: never agree to the asking price. I bought some cheap-looking plastic add-on to my glasses that would flip down and cover them with dark lenses. When I asked the price, the woman said it was 120 Yuan ($15). Without consulting Ken or his friends, I countered with Y30 (about $4)–which was a mistake. Kitty and Flavour showed surprise, saying it was worth only Y5 or Y10 (I simply hadn’t expected the lady to mark up the price that much). I then haggled it down to ten (the ultimate bargaining chip is to start to leave, which is when they almost always cave in), but the lady was pissed, though trying not to show it in her expression. When I paid, she gave me back change so that she kept Y30. When I again insisted on ten, she complained that I’d said thirty, and tried to give me back only another ten so she could keep twenty, but I finally got all the change back from her. A rather inauspicious start to my haggling experience, but instructive.

It was kind of funny how some things worked. A lot of people were selling watches (including a hilarious watch with Mao waving his hand), and the hawkers would show you what was on display; when you showed non-interest in them, the hawker would look around and whisper conspiratorially, “Rolex?” and uncover a box full of Rolex knock-offs, crowing as if this were valuable treasure and as if dozens of other hawkers had not already shown you their stash.

After the market, we went to Yuyuan, am area with again, a lot of shops–but this time in an area of very nice architecture and a park in the center. This area was more expensive, so we did less shopping and more of just looking around, and stopped for a bite to eat as well. The garden area was nice–there is an apparently famous crooked bridge over the pond, but the architecture, a classic style from centuries ago (from what I could pick up, that is), was the show-stealer.

After the market, we went to Yuyuan, am area with again, a lot of shops–but this time in an area of very nice architecture and a park in the center. This area was more expensive, so we did less shopping and more of just looking around, and stopped for a bite to eat as well. The garden area was nice–there is an apparently famous crooked bridge over the pond, but the architecture, a classic style from centuries ago (from what I could pick up, that is), was the show-stealer.

Later, Ken and I met up with another friend of his, Jasmine, who speaks amazingly good English despite never having traveled (apparently it is very hard for ordinary Chinese people to travel abroad), and we bored Ken with a lot of computer talk while we searched for a good restaurant to have dinner at. We were now in Xintiandi (Sheen-tyan-dee, or “New Century”), which is apparently kind of like Roppongi is in Tokyo, a high-priced area where all the foreigners hang out. A lot of nice places, but the prices can be easily ten times higher than local joints–and yet still, a fancy dinner for three came out to about $20 per person, the price of a low-to-midrange meal in Tokyo.

A young girl who agreed to pose quickly for me. She’s wearing a popular headdress, a lot of kids and some adults have them. The girl caught my eye by staring at me–a lot of people do because foreigners are still often uncommon–but they always respond happily when waved back to.

After the night’s festivities, we headed home-but because the outlying light rail shuts down at about 8 pm, we took the bus from Xujiahui. The bus ride, which should have taken half an hour, instead lasted more than an hour, in part because of the same aggressive salesmanship seen in most other parts of the city. On buses, there is a driver and a fare collector. The fare collector sits behind the back door of the bus, and aside from collecting the twenty-five or forty cents from passengers, he spends most of his time leaning out the window shouting at people out on the street. Apparently buses in China are less of a systematic thing and more like taxis, each bus vying to get more warm bodies through the door.

So every few minutes, we would pull aside to a stop–many times not at a stop–and wait between one and ten minutes while the conductor shouted and wheedled. The driver would help out by pulling out a little each time, as if to leave, prompting the prospective customers to hurry up and get on board–so they could wait another five minutes until we actually pulled out from the stop.

Add to this the fact that the buses seem to have no shocks, the seats are narrow and hard, and for most of the trip the malfunctioning backup beeping signal was going off in our ears, and the bus experience is not nearly as nice as it could be.

Begging is also something that you see a fair amount, often a woman and her child, with the child asking for the money. The most noticeable account was on the train into Xujiahui, when a woman led her boy, perhaps eight years old or so, through the train, the boy calling out for alms. This pair saw a great deal of success, mainly due to the fact that the boy was badly deformed. This was not too different from what I experienced in Spain, minus the kid.

But the trains are otherwise a pleasant alternative. They are cheap (usually about 40 cents), come often when they are running, have comfortable seating, and are clean. The down side is the early shutdown, added to the sparseness of train lines. In a city of millions, perhaps on par with a good part of Tokyo, Shanghai has only a handful of train lines to Tokyo’s multitudes. But more are being built; Shanghai is quickly building up and up and up. You can see this especially in the construction of housing. Massive forests of apartment/condo blocks are everywhere, and just as many seem to be under construction.

Between and among these towers ride a large number of two- and three-wheeled bikes, manually or fuel-powered. In many cases, on most large roads, they have an adjacent side road (as big as a medium-sized road in Japan all by themselves) reserved for them. But at intersections, the bikes and cars mix dangerously, each vying for control of their part of the road. Even for someone like me, now well used to traffic in Tokyo, this place seems chaotic and dangerous, taxis sweeping in and out everywhere within inches of bicyclists, pedestrians weaving between slow-moving traffic, hastily getting out of the way of taxis which seem intent to go on through despite human obstacles. Not the perfect traffic environment, but survivable (hopefully) for another six days.