Making Gyoza

Okay, settle down here, because this will be a long post–not necessarily in words, but in inches (or centimeters, as the case may be. A friend recently taught me how to make gyoza (sometimes spelled ‘gyouza’), often called ‘potstickers’ in English. They are essentially a vegetable mix, with meat optional, encased in a small dough wrapping and steamed or fried before serving. I like gyoza, but the ones I get at stores tend to be far less than satisfying–but I found that I really like the homemade ones. The ones I’m showing today are made with chicken. Please note that the amounts of ingredients are approximate–they can easily be increased or decreased to suit your taste. Keep in mind I am no cook, nor a cookbook writer, so this could be a bit messy! Here is the basic setup for cooking:

1/2 head of cabbage or less (you won’t use it all by a long shot, but usually you can’t buy less)

1/2 onion

part of a clove of garlic (use however much you prefer)

one bunch “nira” (leeks)

one bunch “negi” (umm… also leeks, but a different kind. I like the thin type, shown above)

1 to 3 packages large gyoza wrappings (depends how many you plan to cook now)

Sesame oil (“gomayu”)

Seasonings (I use salt and pimenton)

Ground chicken meat (around 250 grams, or half a pound, roughly)

You’ll also need a little flour with water, a largish mixing bowl, a long, sharp knife, a regular spoon, and a frying pan with a cover. Keep in mind that these are just the suggested portions. You can change the amount of any ingredient to your taste, and even add or subtract filling ingredients.

First, slice some cabbage, perhaps three or so quarter-inch thick slices from the middle of the head. Discard any bulky pieces too close to the stem, then start chopping, until you’ve reduced it to tiny pieces. The amount you’ve chopped should amount to about a cup, slightly packed. When finished, throw them into the mixing bowl.

First, slice some cabbage, perhaps three or so quarter-inch thick slices from the middle of the head. Discard any bulky pieces too close to the stem, then start chopping, until you’ve reduced it to tiny pieces. The amount you’ve chopped should amount to about a cup, slightly packed. When finished, throw them into the mixing bowl.

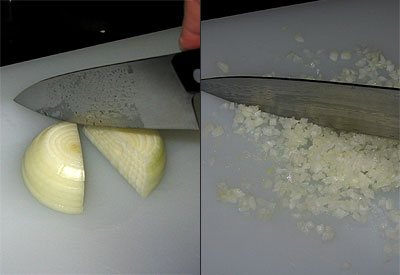

Next, take half an onion (just a regular white onion), and chop it into similarly small pieces. Then throw those into the bowl, too.

Next, take half an onion (just a regular white onion), and chop it into similarly small pieces. Then throw those into the bowl, too.

Then chop the leeks, not just slicing the bits off, but chopping those into finer bits as well. Each type should produce about a quarter of a cup. Into the mixing bowl they go.

Take whatever amount of garlic, if any, that you prefer–I took three lobes, or whatever you call them–and grate/crush them. Add this to the mixing bowl as well.

Take whatever amount of garlic, if any, that you prefer–I took three lobes, or whatever you call them–and grate/crush them. Add this to the mixing bowl as well.

This is what you should have by now.

Now, for the meat, I like to use ground chicken. Ground beef was way too dry; ground pork was OK, but chicken makes the gyoza much juicier, in my humble gourmet opinion. I use the fattier ground chicken, in fact.

Update: At this point, you may want to add cheese. I have found that shredded cheese, added to taste, can make the gyoza even more tasty. I use mozzarella, grated, about half a cup.

After the chicken is added, top it off with the seasonings you prefer. Salt and pepper are safe bets. I use pimenton (smoked Spanish pepper spice) because, well, I use it on everything. So on it goes.

After the chicken is added, top it off with the seasonings you prefer. Salt and pepper are safe bets. I use pimenton (smoked Spanish pepper spice) because, well, I use it on everything. So on it goes.

Finally, pour on some sesame oil. Don’t be stingy, but don’t create a flood, either. Maybe 1/4 cup or so will do, though I’m just estimating here. And then–eeewwwwwww!!–go in with both hands and squish, squash, and knead all of it together until it is well-mixed. Then go wash your hands, for god’s sake!

OK, here are the shells to use. They come in different sizes and thicknesses. I always go for the large ones, partially because I like big gyoza, but also because the smaller ones create a lot more work–you have to make more, and as you’ll see, the shell crimping can be time-consuming. I have no preference between the thick and thin types. Here I am using the thin ones. You can usually find them in your (Japanese) supermarket near the ground meats; if not, ask. The ones I use come in packages of 20.

OK, here are the shells to use. They come in different sizes and thicknesses. I always go for the large ones, partially because I like big gyoza, but also because the smaller ones create a lot more work–you have to make more, and as you’ll see, the shell crimping can be time-consuming. I have no preference between the thick and thin types. Here I am using the thin ones. You can usually find them in your (Japanese) supermarket near the ground meats; if not, ask. The ones I use come in packages of 20.

Have the gyoza filling mix in the mixing bowl handy, as well as an empty plate to put the finished gyoza. Get a small dish or saucer, and put a small amount of flour (a teaspoon, perhaps, no more) onto it, then add a little water; mix some flour into the water until it becomes milky, but not very thick. Open the gyoza shell package, and take out some of the round shells; we’re gonna wrap some potstickers!

Have the gyoza filling mix in the mixing bowl handy, as well as an empty plate to put the finished gyoza. Get a small dish or saucer, and put a small amount of flour (a teaspoon, perhaps, no more) onto it, then add a little water; mix some flour into the water until it becomes milky, but not very thick. Open the gyoza shell package, and take out some of the round shells; we’re gonna wrap some potstickers!

Here comes the difficult part of the recipe; it may take you several attempts to get decent at it, so be patient. First, take a shell into the palm of one hand, and then spoon out some gyoza filling into its center; see the photo above for the amount. Less than a spoonful to be certain–for the first few, less is better than more (when you close the shell, a few steps later, there should be maybe a third or half an inch of border around the filled center). There’s lots of filling here, so go ahead and waste a few if needed.

Next, dip the tip of your finger into the flour-water, and apply this to the border of half the gyoza shell (the same side the filling is on), so as to mark out a semi-circle. Only spread enough with your finger to cover the surface of the edge and make it sticky; it should not run wet. This acts like a glue, and is to get the shell to stay closed. In the photo above, I have set the shell on the cutting board only because I needed a hand free to snap the photo; usually, I wet the edges while holding the shell in my other hand.

Next, dip the tip of your finger into the flour-water, and apply this to the border of half the gyoza shell (the same side the filling is on), so as to mark out a semi-circle. Only spread enough with your finger to cover the surface of the edge and make it sticky; it should not run wet. This acts like a glue, and is to get the shell to stay closed. In the photo above, I have set the shell on the cutting board only because I needed a hand free to snap the photo; usually, I wet the edges while holding the shell in my other hand.

Next can be the trickiest part:

You’re going to have to close the shell, but not just in a smooth, straightforward manner. You will have to crimp one side of the border, making creases along the way. Different people have different techniques for this. My way is to bring the two halves of the shell together and close them just at the center point, leaving the sides temporarily open. Then, working from the top/center, I take some slack from the far side of the shell (as you see in the above illustration, I start on the right side), creating the crease–then pressing down hard to seal them together. I do this twice on the right, and twice on the left, for four creases; you do what suits you.

You’re going to have to close the shell, but not just in a smooth, straightforward manner. You will have to crimp one side of the border, making creases along the way. Different people have different techniques for this. My way is to bring the two halves of the shell together and close them just at the center point, leaving the sides temporarily open. Then, working from the top/center, I take some slack from the far side of the shell (as you see in the above illustration, I start on the right side), creating the crease–then pressing down hard to seal them together. I do this twice on the right, and twice on the left, for four creases; you do what suits you.

The finished product should look something like this:

Note the creases in the shell are only on the one side (call it the “top” now), and the other side should be flat. Note also that the filling should not come close to the edge, with a 1/3 or 1/2 of an inch border.

Continue dalloping, gluing, folding, crimping and pressing, until you have the desired number of gyoza. Usually 12 or so are enough for someone with a good appetite; Hiromi, my friend Ken and I found that 40 gyoza serve three people quite nicely, along with a salad and drinks. The amount of filling that this recipe generates is enough for 40 gyoza, possibly 45 (or even 50 if you use less filling in each). If there is filling left over after you finish (as I had tonight), then drop it into a ziploc and refrigerate it; more gyoza for tomorrow!

In the end, your plate might look like this:

I made 14 here, just for myself (me, hungry).

Now, prepare the frying pan by pouring a small amount of oil (olive oil would be great here) into the pan, then spread it around with a square of paper towel; there should be enough to slightly ‘wet’ all the gyoza as you place them down. Do not pour so much that the whole pan bottom is covered; to the contrary, keep it very light, so that all the oil can be absorbed easily into the gyoza.

Now, prepare the frying pan by pouring a small amount of oil (olive oil would be great here) into the pan, then spread it around with a square of paper towel; there should be enough to slightly ‘wet’ all the gyoza as you place them down. Do not pour so much that the whole pan bottom is covered; to the contrary, keep it very light, so that all the oil can be absorbed easily into the gyoza.

Next, place the gyoza into the pan; up to twenty should fit at a time. Don’t worry if they touch. Fry the gyoza at low heat without a cover, until the bottom of the gyoza are brown; then raise the heat a touch for a moment. Then, with the pan cover in one hand, take a cup of water in the other and pour it into the frying pan, then quickly cover the top as the water turns to steam.

Keep the top on for five minutes at least, perhaps more, checking periodically; when the water has all but steamed off and there is just a bit of water and oil left in the pan, the gyoza may be done. If the water has gone but you think more cooking may be in order, add a bit more water and cover again.

When the gyoza are done, take the pan to your kitchen sink. Drain any excess water (there shouldn’t be any if you did it right), then uncover the pan, and put a dinner plate, upside-down, over the gyoza. Holding the plate with one hand, turn the pan over with the other, then remove the pan from atop; the gyoza should now be nicely placed on the plate.

When the gyoza are done, take the pan to your kitchen sink. Drain any excess water (there shouldn’t be any if you did it right), then uncover the pan, and put a dinner plate, upside-down, over the gyoza. Holding the plate with one hand, turn the pan over with the other, then remove the pan from atop; the gyoza should now be nicely placed on the plate.

Congratulations–you’ve got gyoza! Gyoza need a dipping sauce, so in a small saucer, pour some soy sauce, and then some sesame oil. I top that with (of course) a little pimenton. Serve the gyoza from the central plate, allowing everyone to take from it and dip in their saucer.

Enjoy!

Every five years, you have to renew your Alien Registration Card (aka Gaijin Card, or Gaikokujin Torokusho); I just got mine renewed today. (Image at left–sorry for all the distortion, too much personal info there.) For those of you not in the know, all non-Japanese are required to carry these gaijin cards at all times; if a policeman stops you and you don’t have it on you, then by rights he can take you in to the police station, where you must write a “gomen nasai” letter. You also have to get someone to bring in your gaijin card before you can go. If there is no one to bring your card in for you, you must give the police the keys to your place, and they will get it for you–unless they are kind enough to escort you home while you get your card out for them (happened to me once). Foreigners don’t get stopped just for being foreigners as much as we used to, but it still happens from time to time.

Every five years, you have to renew your Alien Registration Card (aka Gaijin Card, or Gaikokujin Torokusho); I just got mine renewed today. (Image at left–sorry for all the distortion, too much personal info there.) For those of you not in the know, all non-Japanese are required to carry these gaijin cards at all times; if a policeman stops you and you don’t have it on you, then by rights he can take you in to the police station, where you must write a “gomen nasai” letter. You also have to get someone to bring in your gaijin card before you can go. If there is no one to bring your card in for you, you must give the police the keys to your place, and they will get it for you–unless they are kind enough to escort you home while you get your card out for them (happened to me once). Foreigners don’t get stopped just for being foreigners as much as we used to, but it still happens from time to time. After getting my new gaijin card, I left the shiyakusho (city hall) and saw a group of people dressed just like the illustration at right. These are the Japan Tobacco “Smokin’ Clean” clean-up team. Japan is getting better and better about smoking, but is still a relative smoker’s paradise. Many restaurants have no-smoking sections, but the smoking sections prevail, and are in nicer areas. Most workplaces, banks, rest areas and other public places are still smoking havens; the major exception is train platforms, which recently became entirely smoke-free.

After getting my new gaijin card, I left the shiyakusho (city hall) and saw a group of people dressed just like the illustration at right. These are the Japan Tobacco “Smokin’ Clean” clean-up team. Japan is getting better and better about smoking, but is still a relative smoker’s paradise. Many restaurants have no-smoking sections, but the smoking sections prevail, and are in nicer areas. Most workplaces, banks, rest areas and other public places are still smoking havens; the major exception is train platforms, which recently became entirely smoke-free. The whole “Smokin’ Clean” campaign (when you hear it on television, it sounds like “Smo-kin’, CREEEN!”), aside from being a rather glaring oxymoron, is supposed to address the bad manners smokers are often famed for here, particularly littering. Japanese streets, of course, are far less tidy than is commonly believed overseas, and the major component of that street trash is from cigarettes. I long ago formed, tested and proved (well, to myself anyway) the theory that you could go to any place on any street in Japan at random, stop, and when you look around, see at least half a dozen cigarette butts laying there, often many more.

The whole “Smokin’ Clean” campaign (when you hear it on television, it sounds like “Smo-kin’, CREEEN!”), aside from being a rather glaring oxymoron, is supposed to address the bad manners smokers are often famed for here, particularly littering. Japanese streets, of course, are far less tidy than is commonly believed overseas, and the major component of that street trash is from cigarettes. I long ago formed, tested and proved (well, to myself anyway) the theory that you could go to any place on any street in Japan at random, stop, and when you look around, see at least half a dozen cigarette butts laying there, often many more. This fellow is often seen standing by a pillar on the very busy basement-level area outside the West Exit of Shinjuku Station. A monk in traditional garb, holding a begging (alms) bowl, with the trademark monk’s hat (“Takuhatsu gasa”). Whenever someone drops some money into his bowl, he rings a bell.

This fellow is often seen standing by a pillar on the very busy basement-level area outside the West Exit of Shinjuku Station. A monk in traditional garb, holding a begging (alms) bowl, with the trademark monk’s hat (“Takuhatsu gasa”). Whenever someone drops some money into his bowl, he rings a bell. I don’t use the secondhand shops today nearly as much as I used to, but they can be a real boon to those of us starting out in Japan, or here for the relative short term. It’s sometimes hard to find any shops like that worth visiting, though.

I don’t use the secondhand shops today nearly as much as I used to, but they can be a real boon to those of us starting out in Japan, or here for the relative short term. It’s sometimes hard to find any shops like that worth visiting, though. The entire chain seems to have shops all around Tokyo, in places like Itabashi, Sasazuka, Okubo, Suginami and a few other locales. You can visit their

The entire chain seems to have shops all around Tokyo, in places like Itabashi, Sasazuka, Okubo, Suginami and a few other locales. You can visit their

OK, I am now officially getting screens for my windows, or else finding some other way to keep cool for the summer. Did I ever mention that large insects completely freak me out? They do. Under a few centimeters in length, I got no problem. But if they’re as big as a medium-sized cockroach, I start to climb the walls. Call it a weakness. I just hate ’em.

OK, I am now officially getting screens for my windows, or else finding some other way to keep cool for the summer. Did I ever mention that large insects completely freak me out? They do. Under a few centimeters in length, I got no problem. But if they’re as big as a medium-sized cockroach, I start to climb the walls. Call it a weakness. I just hate ’em.