Dead Pixel, Stuck Pixel, Dim Pixel, Fine Pixel

As I mentioned before, when I got my new 24-inch iMac, my initial worry was dead or stuck pixels. I thought there was one dead one, but now I’m not so sure. Let me explain from the beginning.

A “pixel” is named after the words “picture element,” and refers to a single dot on a computer display. It’s an element because you can’t divide it further (in one sense). Each dot, or pixel, has its own unique color. Your display’s image is made up of perhaps over a million such dots. The computer generates the display image by telling each pixel exactly which color it should take for any given refresh of the screen, and there are perhaps 60 or so refreshes per second.

The old, heavy CRT monitors “painted” the pixels on the screen, line by line, and could change the number of lines (rows of pixels) flexibly; this allowed them to change resolution (number of pixels on the screen) and still maintain a sharp, clean image. Because they “painted” the pixels with color guns, you never had problems with individual pixels on CRTs; instead, if one of the guns failed, you’d have a discolored screen.

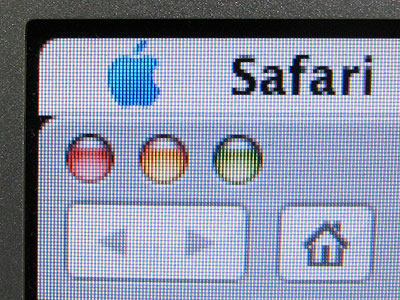

The new, thin LCD monitors work differently. In these monitors, each pixel is a physical entity on the screen; each pixel is its own mechanism. If you peer really, really closely at your LCD screen (preferably on a white area), you might just be able to squint and see the tiny lines, little rows and columns of teensy little squares. Those are the physical pixels of the LCD monitor. Here’s an image to save you some squinting:

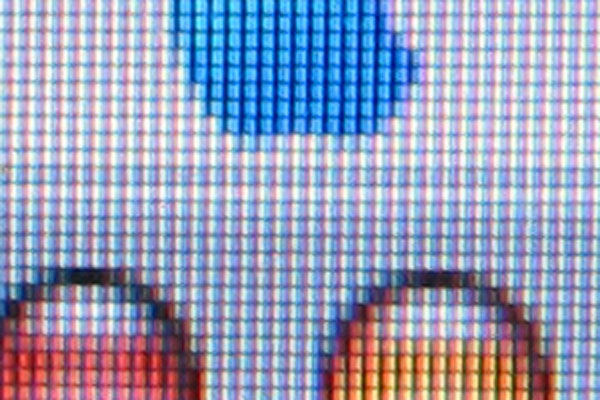

Now, getting closer…

And closer yet…

![]()

Now you can see what a pixel on an LCD is really like. As you can see, each pixel actually has a red, green, and blue element. Those colors are the primary colors of light. By changing the brightness of each of the three colors from zero to full, you can create any color the human eye can see. For example, if you turn the red and green pixels on full and turn off the blue pixel, you get yellow. Turn on the red and the blue and turn off the green, it’ll be purple (magenta). Turn all three on full, it’ll be white; turn all off, and it’s black.

So actually, each LCD pixel has three parts to it, each one working independently. My LCD screen has 1920 x 1200 pixels, or 2,304,00 pixels. Count the color elements, and the LCD screen has 6,912,000 working parts.

We whine about dead and stuck pixels, but when you consider it, the ability to make a very expensive single piece of equipment with almost seven million working parts and not a single one of them failing–well, that’s one hell of an accomplishment, when you think about it. Frankly, it’s amazing they can make such screens without any malfunctioning pixels.

But parts do come out bad, and that’s what we have to deal with. The two most common ways for an LCD screen to have something wrong is with “stuck” pixels and “dead” pixels. In each case, it is commonly not the entire pixel, but usually one color element within the pixel that goes bad. In a “stuck” pixel, one of the color elements turns on and never turns off until the monitor is shut down. A “dead” pixel is the reverse–the color element, or sometimes the whole pixel, remains dark. Here are a few examples of “stuck” pixels:

Stuck pixels show up best against a dark screen, so you’ll notice them most when you’re watching a video with dark scenes.

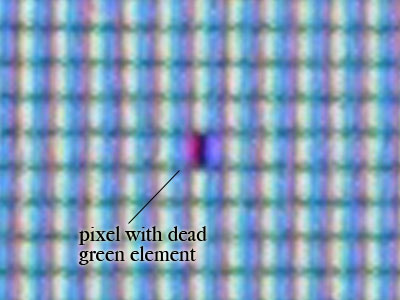

A “dead” pixel will appear to be a tiny speck on your screen–you will often mistake it for a bit of dust, or conversely, you’ll mistake a piece of dust for a dead pixel. Here’s one that was on my Powerbook screen, before I had it swapped out last month:

Only the green element was dead, not the whole pixel.

So, getting back to the subject I started with, my new iMac. When I got it, I noted that there was one dead pixel up near the top left of the screen, apparently with the green element out. It seemed even smaller than I had seen a dead pixel look like before. At first I thought it was the larger screen and the pixels were smaller, but that’s not the case–Apple keeps the pixels about the same size.

So I decided to photograph it, that being the best way to see tiny details too small for the naked eye. Strangely, the photos showed no dead pixel elements. I looked at the monitor with my eyes, and sure enough, there was the dark dot. What the?

I started up Photoshop, and created a red, green, and blue image. By moving each color over the malfing pixel, I could see which elements might be mucked up. Sure enough, when I looked at the blue and the red, the dead pixel “disappeared”; when I put it on green, the dead pixel stood out. It was the green element, all right.

So why were my photos showing no dead pixels? After a bit of experimenting, I found out why: the pixel’s green element isn’t dead–it’s dim. I’d never heard of that before, but there it is. Here’s an image of the pixel with a green image; the red and blue elements will be dark, accentuating the green. You have to look carefully to see the one green element that’s dimmer than the others.

![]()

Can you see it? It’s on the same pixel row as the horizontal bar of the “plus” cursor, with the arrow pointing at it.

Frankly, I’m amazed I even noticed it with my naked eyes–I must have pretty good vision. That explains why it’s not so dark as a dead pixel, and probably why I have to strain to even see it. I never even knew pixels could be permanently dim like this–now I do.

There might be some variation in the width of the vertical structure, causing the size of each element to vary a little. The thing you refer to might be within spec.

Jeeze, I would never have noticed it … *looks again* … I can’t even see it now, in your example!

While I’ve been aware of pixels and such for a loooong time, I was only vaguely cognizant that a single pixel actually consists of the three colour elements SIDE-BY-SIDE. And I don’t understand how that works; why doesn’t the eye see a pixel as three separate sub-pixel sized bits of disjoint colour?

If you get paint of different colours and MIX UP the paint – into one single mess – then you have as a result the final conglomorate/compound colour. I always thought LCD pixels worked something like that (the elements ‘on top’ of each other, somehow). But an LCD pixel doesn’t do that – they’re sitting there, side by side. Is it just a fact that the brain merges them all together if the light sources are small enough? Seems very untidy to me.

Can the LCD sub-pixel elements be turned on at various strengths or intensities?

One last question – I asked before about using e-mail addresses here on your blog, and did it once, expecting to get messages e-mailed back when you or anyone else responded to a blog ‘thread’. That didn’t happen, though. And you’re so prolific it’s a real problem going back to see if you’ve said something in response to a comment. Can you tell me if the e-mail addresses are used in any sort of ‘notification’ mechanism, or if such exists? I’ll try to find this blog entry again to see if you respond!

Brad